In 2024 I created a sequence of unique Christmas cards that formed an animation:

I ended the story of their creation with:

I strongly suspect next year’s cards will be a little simpler…

… but, seen as you’re back here, it should be fairly clear I failed.

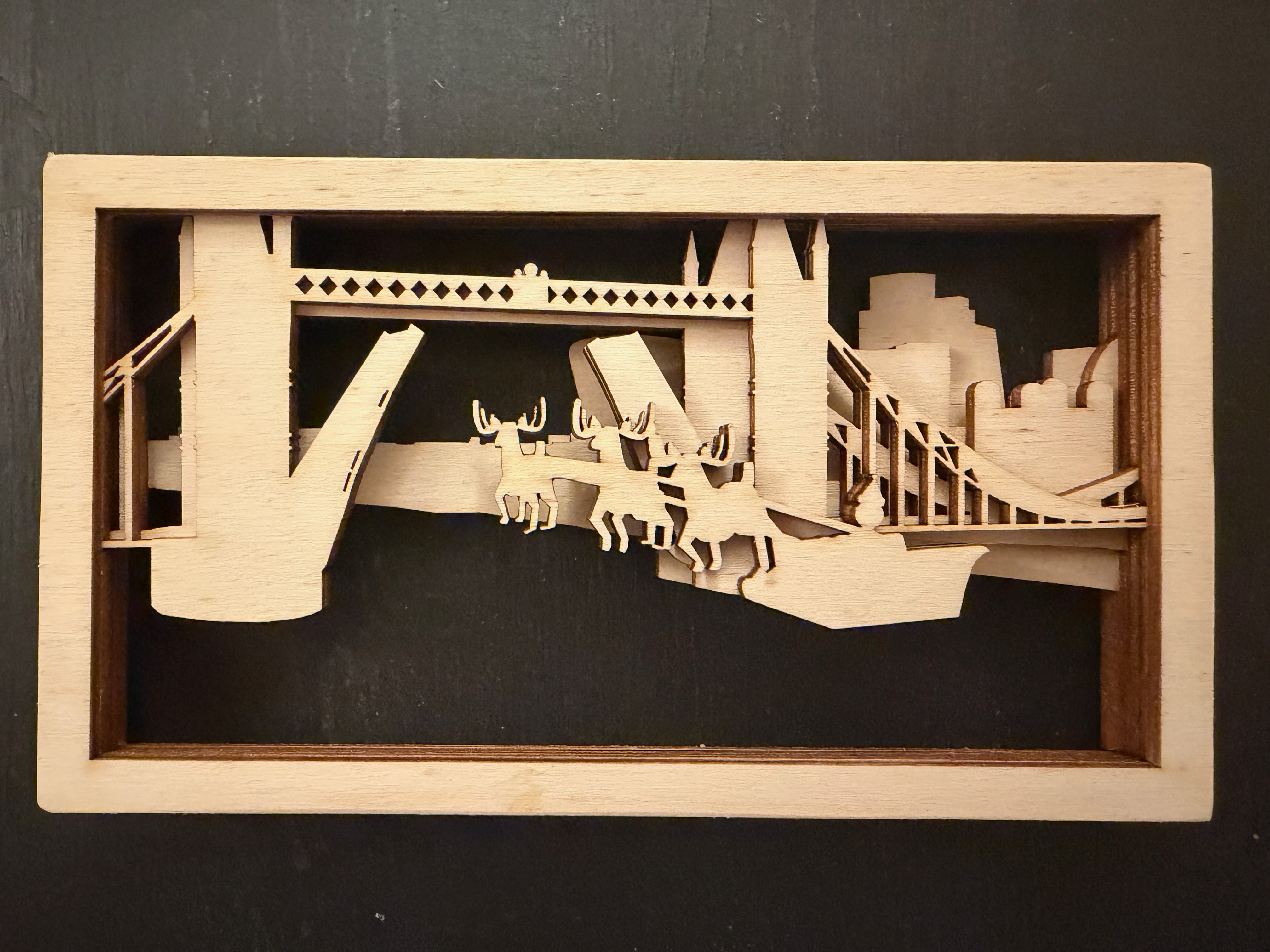

Last year’s cards were individually static and unique, but moved together. My goal this year was to invert that: a single design where each card moves. A hand-driven advent clock.

I started developing ideas for this year’s card back in August. Quite early on I liked the idea of building a gear based card where you provide the motion for the card, again inverting the relationship. Gears lead me to clocks, and I spent an afternoon sat basking in the sun by a lake in rural Sweden getting ChatGPT to suggest ideas for a “Christmas clock”:

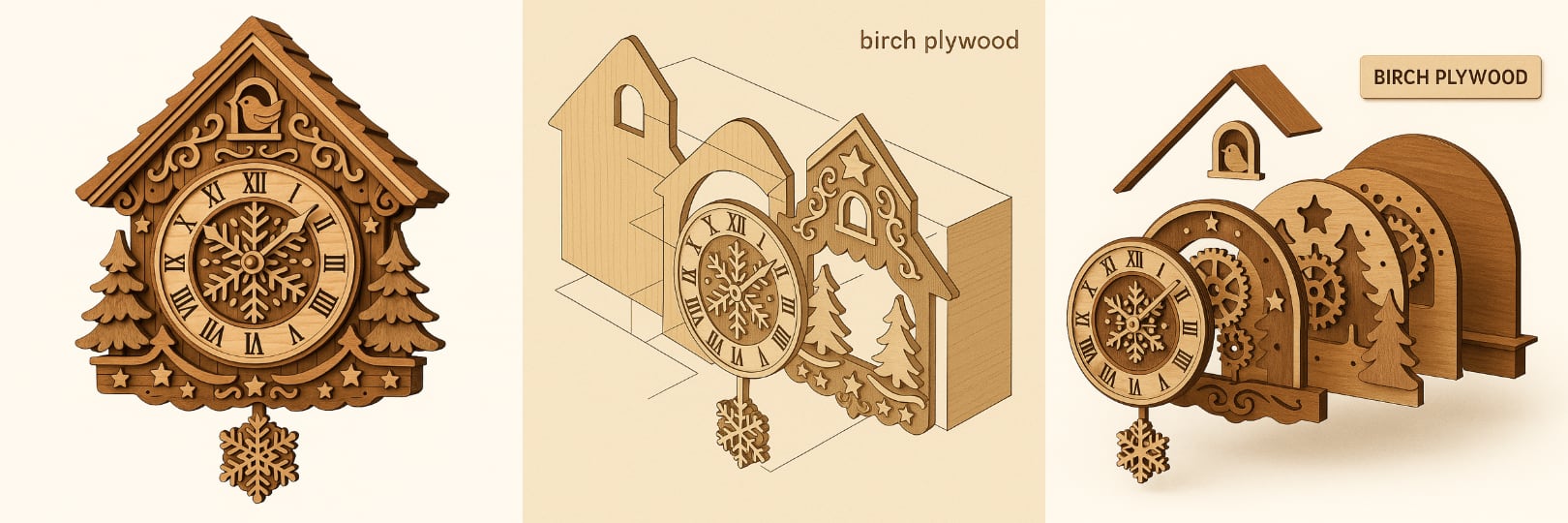

I was also keen to switch up the materials used. My original idea for last year’s card was to cut thin wood veneers rather than card, but I knew I’d need something thicker to support the gears. Early in the autumn I commissioned Lightning Laser in Gloucestershire to cut a copy of last year’s card in birch plywood:

This convinced me that it would be worth pursuing a wooden frame, perhaps with engraved details. However, two problems remained: how would I design a clock mechanism, and how would I make its parts?

The correct answer to the first problem would’ve been to make a concerted effort to learn the basics of CAD software and use built-in tools for generating gear shapes. But when I started in earnest in late October I wasn’t convinced I’d have time to learn CAD in time for Christmas.

Now here’s the thing: I’m alright at maths and I know a thing or two about computer graphics. So over the course of a few long train journeys I gradually taught myself how to precisely compute the shape of idealised gears.

And so a few thousand lines of JavaScript later I had a fully parametric design that allowed me to shift the gears around and play with design ideas. Through this process I did a ton of trigonometry and derived involutes to calculate the shape of each gear tooth. For several weeks I had dozens of tabs open describing all sorts of gears as I gradually turned them into code, and the code into the frames that could be laser cut.1

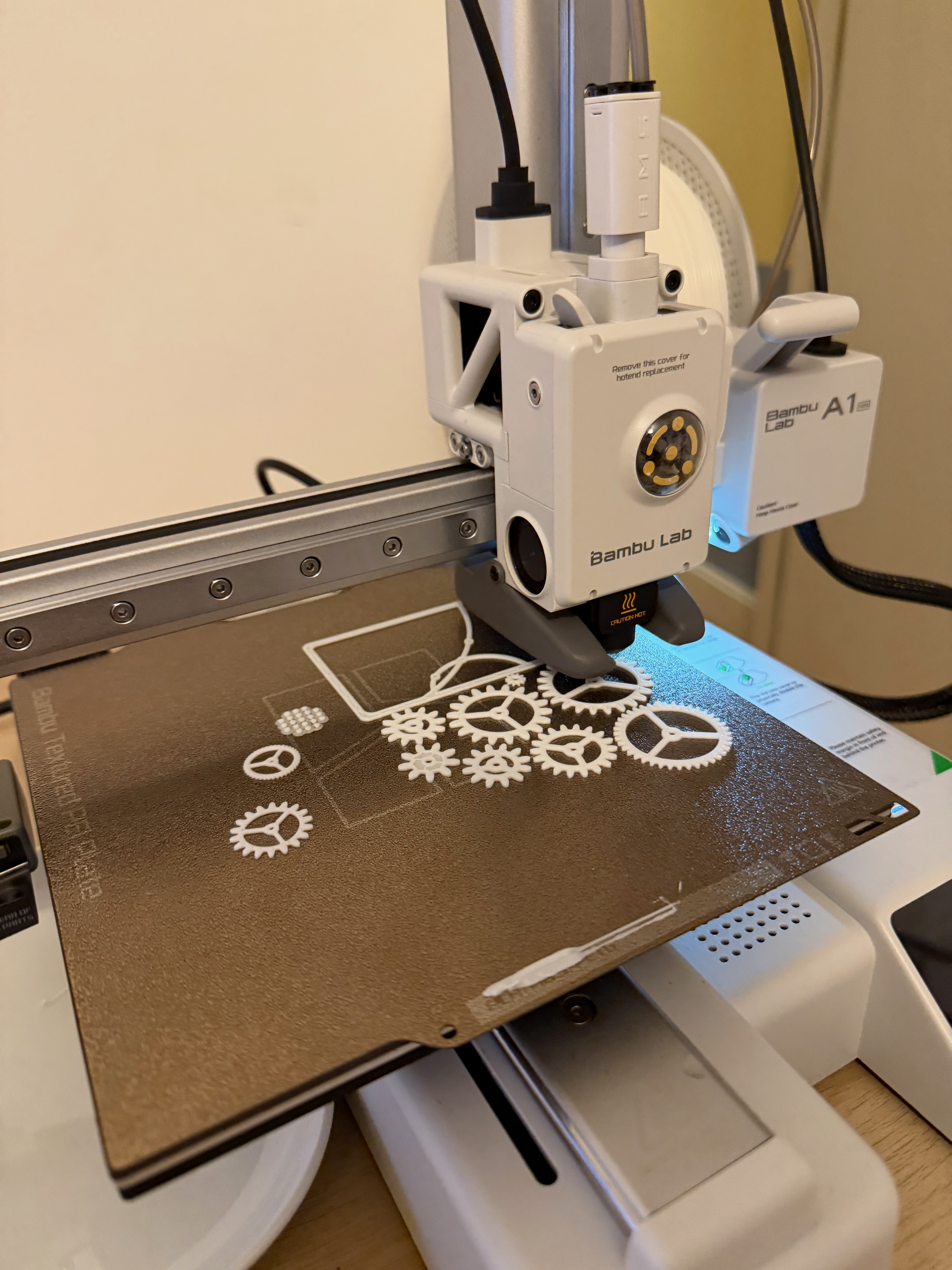

The next problem was how to make all the gears. A friend pointed me to Bambu Lab’s Black Friday sale.2 I picked up an A1 Mini — an entry level 3D printer — for £140 and then proceeded to thoroughly abuse it with over 100 hours of total printing to make all the gears.

Before this project I had no experience with 3D printing. I was genuinely stunned how straightforward it’s become. Until recently it was a highly technical hobby. The vast majority of the parts printed with no trouble at all, and I found it transformative to think of it as literally “printing” things into existence. For most of the parts I just needed to import their shape, set their height, and click print. (For some of the more complex multi-layer parts I used Blender to fuse shapes. That’s not the right tool for the job, but it was the one I knew.)

Designing the front of the card wasn’t too hard. I settled on Big Ben early.3 This left space on the other half of the card for something like a lunar complication. However, I found it difficult to fit all the necessary gears in to step down to such an infrequent rotation. Instead, I created a Geneva Drive to only rotate a date window once per day, for each day of advent.4 I needed somewhere to place the day number, and of course an obvious source of numbering here is London’s buses.

Each wheel of numbers is hand-written, as are the insides of each card. I used an entirely accidental mixture of Robert Oster’s Heart of Gold and J Herbin Emeraude de Chivor with the Lamy 2000 and Pilot E95s. Happily the paper and card elements of each card re-used leftover materials from 2024.

The final stage was to get the cards assembled. In many ways this was more straightforward than 2024, because I was producing identical cards rather than unique, so I could just focus on doing one task on all the cards at once. Like last year, I got through a lot of shows and movies in the background.

To finish them, I also wrapped each card in green tissue paper and red ribbon.

I again spent several hundred hours designing and constructing these cards. Across all the cards there are over 2000 parts, each of which variously required engraving, cutting, gluing, painting, sanding, and writing. I owe a particular thanks to Nick for tricking me into finally getting a 3D printer, Oscar for being my sounding board for the maths, and Oliver at Lightning Laser for working with me on last minute redesigns and finding ways to minimise material waste.

It’s been delightful over the last year to hear and see that so many people kept my 2024 card as part of their family’s Christmas decorations. I hope this year’s is a suitable companion for it.

So, what’s on the cards for 2026? I have ideas.

The basic principles of gear ratios aren’t especially complex, and reasonably easy to derive. I can highly recommend Bartosz Ciechanowski’s visual explanation, along with the rest of his website, which served as a helpful reference for me throughout. I don’t think I ultimately used any mathematical techniques beyond A-level maths or maybe first year university courses.↩︎

Which started in October. Halloween failed us as the bulwark against the encroachment of Christmas and Thanksgiving traditions into the early autumn.↩︎

Ha! You took my footnote bait. I’m obviously well aware of the distinction between Big Ben, the bell, and the Elizabeth Tower itself. I’m guessing you are too. If you’re in London I can highly recommend a tour of the tower and the bell. The tours are timed so that you’re standing next to the bell when it strikes, so here’s a tip: go for the late morning tours to literally get more bongs for your buck!↩︎

I’m using the secular, chocolate advent calendar definition here. Not least because it was easier to create a pair of gears to reduce the frequency of rotation to once every 4 × 6 days.↩︎